Hair Cell Proliferation and Regeneration

Humans and other mammals develop inner ear sensory hair cells embryonically. The only subsequent change in number of cells is due to loss. Cells are never added in mammals, and so loss of cells means hearing loss. In contrast, we found that fishes, like elasmobranchs (sharks and rays), continue to add sensory hair cells to the ear for at least several years after birth (Lombarte and Popper, 1994).

Using the hake, Merluccius merluccius (a relative of the cod), we demonstrated that hair cell proliferation continues in all three otolithic end organs until fish are at least nine years old. As shown in the figure on the left,, the increase in number of hair cells is far greater in the saccule than in the utricle and lagena. The figure shows that the total number of sensory hair cells in all three end organs of a single ear is over 2 million by the time the fish is 70 cm long (or about nine years of age).

We also demonstrated similar proliferation in a cichlid, and there is every reason to believe that the addition of sensory cells occurs in all fishes.

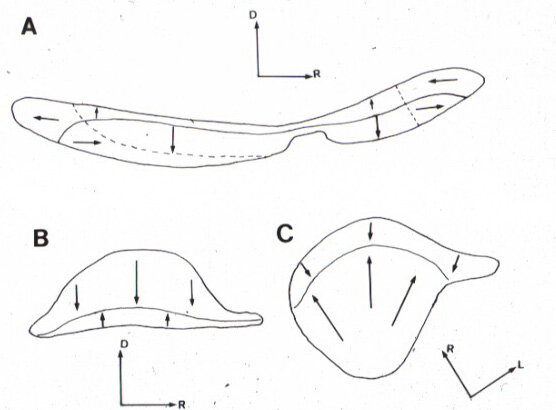

Figure showing growth of the saccular (A), lagenar (B), and utricular (C) sensory epithelia (maulae) in the hake from small animals (top of each figure) to animals that are almost a meter long. The numbers indicate areas of the tissue that were sampled in calculating the number of sensory cells.

We have also shown that if hair cells are destroyed or damaged as a result of treatment with ototoxic drugs or exposure to sound, the hair cells will regenerate. In Smith et al. (2006), we showed that loss of sensory cells is correlated with temporary hearing loss (left) that recovers over several days after the sound is turned off (right). These results are from the goldfish, a species that hears well. In contrast, we have shown that exposure to the same sound level in tilapia (a cichlid), a species that does not hear well, there is no hearing loss or hair cell damage.